Najiba Noori opens “Writing Hawa” in the French sky of 2021. It’s the sky Noori herself gazed at as she fled Kabul, leaving Afghanistan just as the Taliban came roaring back to power. It’s exile in a shot. Afghan journalist-turned-filmmaker descends into Paris on an airplane, and the camera follows her gaze downward — from sky to earth, from freedom to loss. That descent is the film’s lament. Yet what the movie is really about is another kind of movement: a woman’s ascent.

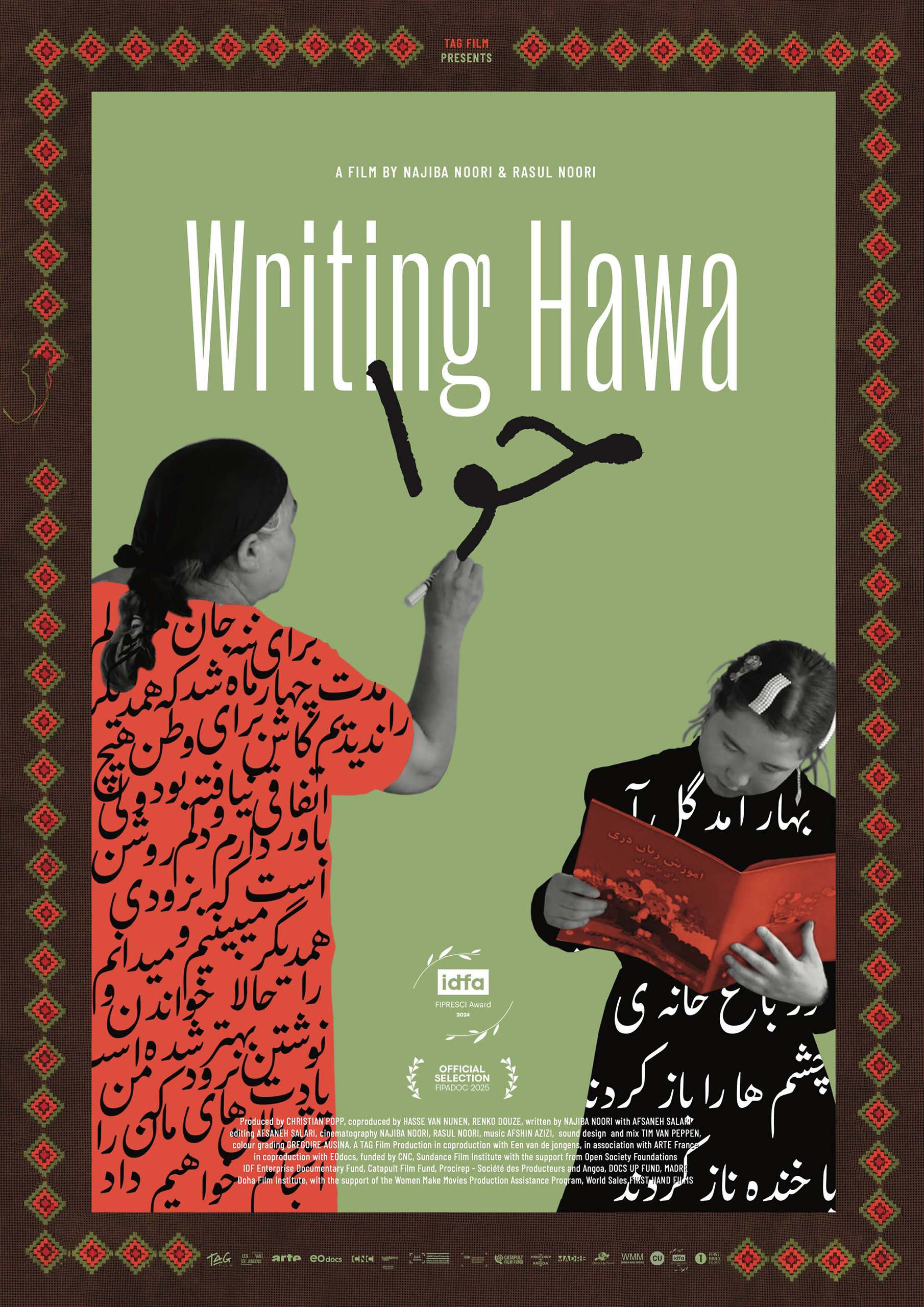

The film, which had its world premiere at the 37th edition of IDFA (where it won the FIPRESCI critics’ prize) before opening earler this month (Seotember 11) in the Netherlands, is Noori’s feature debut, and it’s woven with the intimacy of memoir. Her narration isn’t just commentary — it’s identity. She positions herself as the voice of modern Afghan womanhood, binding together five years of footage that link mother and daughter, past and future, tradition and modernity.

One of the earliest images is deceptively simple: Hawa, Noori’s mother, wrings water from a washed carpet strung on a clothesline. Carpet weaving is Afghanistan’s cultural bedrock, but here it becomes metaphor — as if the old life were scrubbed clean and hung out to dry, making space for something new. That “something” is Hawa herself. Married at 13, denied an education, her life scripted by motherhood, she begins — late in life — to transform before our eyes.

That journey takes forms that are at once small and monumental. Hawa dyes her hair for the first time. She starts to notice her body, giving in to middle age but not surrendering to it. She sets up a business, and begins to achieve a sliver of independence. Noori, by contrast, is the modern daughter — a journalist, educated, outspoken, in control of her voice (literally, since it’s her voice narrating the film). The tension of “Writing Hawa” is the space between those two poles. In a sense, the whole movie is watching Hawa walk — sometimes inch, sometimes leap — toward Najiba.

One of Noori’s most resonant conceits is the act of writing itself. Hawa knows her name but can’t inscribe it. The gap between knowledge and expression — between body and voice — is the gap that defines her life. She knows she is a woman but, in a patriarchal society, has never been allowed to “write” her womanhood. Literacy becomes liberation. Watching her shape letters is like watching someone reboot their own operating system.

The film frames this as a movement from east to west — from tradition to modernity, from blue to red. Those colors run through the film like threads in a carpet. Blue is tradition: control, fear, the weight of patriarchy. Red is modernity, the danger-tinged passion of stepping into something new. And even Hawa’s hijab plays into that story. At home she wears it as tightly as outside, almost as if the walls themselves are public space. Gradually, scene by scene, it loosens. Sometimes it’s gone. That alone becomes a barometer of how far she’s traveled.

At one point her husband, Musa, 30 years older, looks at her and doesn’t recognize the woman standing in front of him. The film makes that moment sting: change can be so total it feels like erasure.

Yet what’s striking is that the film never pretends Hawa is going to turn into some Western poster child of independence. By the end she’s not “modern” in the simplified sense. She’s a woman in whom tradition and modernity are intertwined, stitched together like the knots of a carpet.

But Noori is too savvy to let it all play like a domestic parable. She crosscuts Hawa’s ascent with Afghanistan’s descent. As Hawa gains literacy, the Doha negotiations unfold on TV — America bartering away Afghanistan’s future, paving the road for the Taliban’s return. Editor Afsaneh Salari weaves those scenes in so that they run parallel. The north-south axis of the movie is women rising even as the nation falls. The politics are plain: the West that “supported” Afghan women also made sure they’d be shoved back into darkness. It’s a stinging point, made not with lectures but with juxtapositions that land like body blows.

Then comes Zahra, Hawa’s granddaughter, just 13 — the same age Hawa was when she was married off. Zahra has run away from home. She’s Hawa’s past in the present tense, and she’s also her possible future: Gen Z, rebellious, with at least the idea of freedom. In Zahra’s chapter, the film becomes immediate, almost raw. Hawa buys her a red dress, corrects her spelling of words on a whiteboard. Those moments carry a sweetness — like Afghan kachi, sugar against bitterness — but they’re laced with dread. We know her father will try to marry her off, poison her path. And still, the encounter plants something. If literacy gave Hawa wings late in life, Zahra’s gift is to get the seeds early, even if they’ll take years to grow.

The film circles, again and again, back to exile. It begins with Najiba’s voice over the French sky. It ends with her family leaving Kabul for Iran, eventually joining her in France. Exile is the frame. But exile also defines Hawa’s inner journey: from being illiterate to being able to write, from dependence to some measure of independence. For Afghanistan, too, exile is the condition — from a brief flirtation with freedom back to Taliban repression. For Afghan women, it’s a permanent state: exile from their own choices, from visibility, from the futures they should have had.

Yet for all its symbolic richness, “Writing Hawa” is not without limitations. Noori offers a controlled and sanitized portrait of Afghan society, one scrubbed of the dirt and blood we know is there. Violence exists mostly in absence — referred to on TV, in news reports, or in passing narration. When the Taliban’s attack on her brother Rasul (who is credited as co-director) is reconstructed, the scene feels abstract, more symbolic than visceral, even artificial. Men — apart from Musa — are present mostly as shadows, diminished to the point of irrelevance. That absence is a choice, and a politically pointed one. But it also robs the film of the raw conflict that could have sharpened its stakes. It’s powerful, but also manipulative.

And that’s not necessarily a flaw. If you’re weaving a carpet to be shown abroad, you don’t show every loose thread. You present the pattern. Noori has done that: presented a vision of three generations of Afghan women as a handwoven silk carpet, one that the world can lay out and see. It’s curated, yes, but it’s also authentic in the way art can be: selective but truthful. The carpet is exquisite, the colors vivid, the figures radiant. But beneath the surface, you can sense the strands tucked neatly out of view.

Noori has created a film that may be imperfect, and at times deliberately selective, but one that holds the weight of three generations of Afghan women — woven together like a carpet of exile, survival, and rebirth.

“Writing Hawa”

Release Date: September 11, 2025 (Netherlands)

Production: TAG FILM. Producer: Christian Popp. Co-producers: Hasse van Nunen, Renko Douze.

Crew: Director: Najiba Noori. Co-director: Rasul Noori. Authors: Najiba Noori, Afsaneh Salari. Director of Photography: Najiba Noori, Rasul Noori. Editor: Afsaneh Salari. Original Music Afshin Azizi. Sound Designer: Tim van Peppen. Visual Effects: Filippo Robino.

With: Hawa Noori, Zahra Haidari, Fatima Noori, Musa Noori Rasul Noori, Mahdi Noori, Zaher Noori, Mohammad Ali Khaliqi, Mehran Khaligi, Kian Khaliqi.

France, Netherlands, Qatar, Afghanistan.

84 minutes,

in Dari.